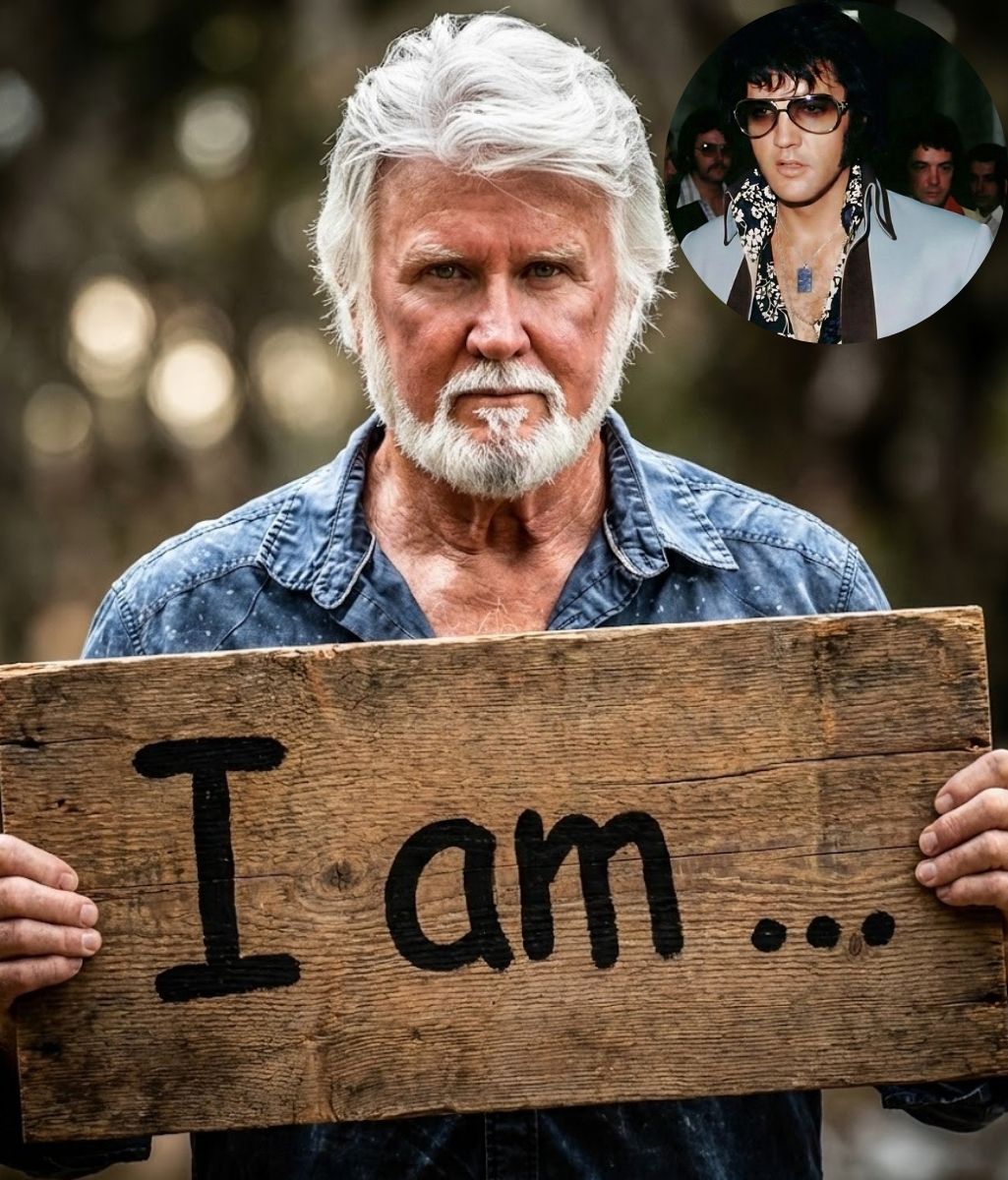

For decades after the world mourned the passing of Elvis Presley, a stubborn rumor has continued to circulate in quiet corners of popular culture. It is the claim that Bob Joyce has admitted to being Elvis himself. The statement is short, sensational, and emotionally charged. Yet when we slow down and examine it with care, the story becomes far more revealing—not about hidden identities, but about memory, longing, and the enduring power of a voice that shaped a generation.

To begin plainly and responsibly: there is no verified evidence that Bob Joyce has admitted to being Elvis Presley. No sworn testimony, no official documentation, no credible interview exists in which such an admission is made. What does exist is a persistent belief, fueled by resemblance in vocal tone, mannerisms, and the deep affection many listeners still carry for Elvis. For some, these similarities feel too strong to dismiss. For others, they are a reminder of how easily the heart can connect dots that history does not support.

Bob Joyce is a pastor and gospel singer, known for his rich baritone and his heartfelt performances in church settings. When recordings of his singing began circulating online, listeners noticed something familiar. The phrasing. The warmth. The resonance. To fans who grew up with Elvis on the radio, these qualities stirred old emotions. Soon, speculation followed. Videos were shared with captions that asked questions rather than offering proof, and over time, questions hardened into claims.

This is where clarity matters. Similarity is not identity. Voices can resemble one another. Musical influences travel across generations. Elvis himself drew deeply from gospel traditions, country hymns, and spiritual music. It should not surprise us that a gospel singer decades later might echo elements of that style. What feels uncanny is often heritage, not disguise.

Yet the rumor persists, and that persistence deserves understanding, not ridicule. For many older listeners, Elvis represents more than a performer. He is tied to first memories of music, to family gatherings, to long drives with the radio humming softly in the background. When someone sounds like Elvis, it can feel as if a door briefly opens to the past. The idea that Elvis might still be alive—still singing somewhere quietly—offers comfort in a world that has changed too fast.

Supporters of the claim often point to selective moments: a pause between words, a familiar vocal turn, a perceived reluctance to seek fame. These observations are interpreted as deliberate concealment rather than coincidence. But interpretation is not evidence. When examined carefully, these arguments rely on emotion, not documentation.

It is also important to note that Bob Joyce himself has repeatedly denied being Elvis Presley. He has stated that he is simply a man devoted to faith and music, uncomfortable with the attention such rumors bring. In measured, calm language, he has emphasized that he does not seek celebrity and does not claim an identity that is not his own. Ignoring these statements while insisting on a hidden confession is not skepticism—it is dismissal.

Why, then, does the headline “Bob Joyce admits he is Elvis Presley” continue to appear? Because it captures attention. It taps into nostalgia. It promises a revelation that would rewrite history. In an age where dramatic claims travel faster than careful explanations, curiosity often outruns truth.

For readers with life experience and perspective, there is value in stepping back. Legends thrive when they are left unexamined. History, however, deserves steadier ground. Elvis Presley’s life, influence, and passing are well documented. His legacy does not need mystery to remain powerful. In fact, it stands stronger when honored honestly—through his recordings, his performances, and the cultural shift he inspired.

In the end, the story is not about a secret survival. It is about how deeply a voice can lodge itself in our shared memory. When we hear something that reminds us of Elvis, we are not discovering a hidden truth—we are revisiting a feeling. And feelings, especially cherished ones, can be persuasive.

So let us be clear and fair: Bob Joyce has not admitted to being Elvis Presley. The claim survives because it speaks to longing, not because it rests on fact. And perhaps that is the most human part of the story. We are a people who hold on. We listen. We remember. And sometimes, when the music sounds just right, we hope.

Video